ΕΦΗΜΕΡΕΣ ΑΡΚΑΔΙΕΣ

Τριάντα χρόνια Βρετανικής φωτογραφίας τοπίου από τη συλλογή του Arts Council

Περιοδεύουσα έκθεση

Συμπεριλαμβάνονται έργα των Lewis Ambler, Keith Arnatt, John Blakemore, Chris Chapman, John Davies, Fay Godwin, Donald Jackson, Paul Joyce, Clive Landen, Raymond Moore, Roger Palmer, Ingrid Pollard and Susan Trangmar.

FLEETING ARCADIAS

I

Oh thou, that dear and happy isle

The garden of the world ere while,

Thou paradise of foúr seas,

Which heaven planted us to please,

But, to exclude the world, did guard

With watery if not flaming sword;

What luckless apple did we taste,

To make us mortal, and thee waste?

Andrew Marvell, Upon Appleton House

Arcadia is both place and ideal. The real Arcadia was and remains the barren, land-locked central district of the Peloponnesus, in southern Greece; the Arcadia of the mind was first invented by Virgil and the Roman poets of the golden age, for whom it became the abode of Pan, an idealised landscape of leafy forests and green meadows peopled by nymphs and shepherds at play in an unending summer twilight. Having become a symbol, Arcadia was resuscitated at the Renaissance as a paradigm of idealised nature, uncorrupted and benevolent.

Such idealisation, however, contains within itself the seed of doubt, exemplified by Poussin’s famously ambiguous pair of paintings, Et In Arcadia Ego; “Even in Arcady Was I” expresses nostalgia for the classical world, but the speaker may also be the personification of Death. Later, the worm in the bud was identified with man himself, whose sinful and imperfect nature cannot but corrupt all about him. Writing in 1650, Andrew Marvell described England as ‘the garden of the world’, while lamenting the human propensity for destruction; ascribing this propensity to original sin conceded its apparent inevitability.

II

From whatever cause it proceeds, certain, I believe, it is, that this country

exceeds most countries in the variety of its picturesque beauties.

William Gilpin, Observations, relative chiefly to picturesque

beauty, made in the year 1772, on several parts of England

It is, above all, a small-scale, asymmetrical landscape, of small,

irregularly shaped fields, old hedges, winding lanes, deep

ditches, banks, moats, oddly-shaped copses and old trees.

Richard Mabey, In a Green Shade: Essays on Landscape (1983)

It was in Britain that the arcadian ideal became most firmly rooted in national consciousness, acting as both metaphor and consolation. Metaphorically, the undefiled purity of the natural landscape has traditionally been contrasted with the corrupting works of man, while that same apparently unchanging purity has been an important source of spiritual comfort, confirming an essentially conservative system of values.

This tradition, together with the peculiarly tactile quality of light in these islands, ensured that landscape rapidly became one of the most popular of British photographic genres, exemplified by the work of artists as diverse as Calvert Jones, P.H. Emerson and Bill Brandt. What almost all this work had in common was a celebratory quality, often producing images of great beauty and subtlety. Until the mid-1970s, British photography’s preferred approach to landscape was either lyrical or sublime – responses predicated on an presumption of innocence in the medium no less than the subject.

III

Every architectural move is set in a landscape strategy.The eighteenth-century

grid cities of the New World are a strategy of reason, for example.Norman England

was constructed as a network of strong points, in a strategy of occupation.

Our predominant landscape strategy now is the economic exploitation of the earth.

Paul Shepheard, The Cultivated Wilderness (1977)

There is nothing natural about British landscape, every square foot of which is the result of human intervention over thousands of years, from the open field system of Saxon England to the drainage of the fenlands which began in the 1700s. The pace of change accelerated dramatically in the 20th century, with increasing urbanisation and the development of agribusiness contributing to the final breakdown of traditional rural order. Inevitably, as rural communities disintegrated, photographic depictions of landscape became increasingly elegiac, dwelling nostalgically on ruins or hurrying to record vanishing folk customs.

The first challenges to this supposedly ‘transparent’ approach to the photographic depiction of landscape depended on the quintessentially British rhetorical device of irony. Raymond Moore subverted the genre by concentrating on enigmatic signs and fragments, humble visual paradoxes which, as Ian Jeffrey realised, “call history and the social hierarchy into question”. Within a few years, Ian Walker was to develop a deadpan typology of Little Chef restaurants, aggressively replicating pustules on the landscape of the sublime.

IV

We have done unimaginably dreadful things to our

countrysides in these last fifty years.

John Fowles, essay accompanying Fay Godwin’s Land, (1985)

The arcadian idyll seems just another pretty lie

told by propertied aristocracies (from slave-owning

Athens to slave-owning Virginia) to disguise the

ecological consequences of their greed.

Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory (1995)

Two developments in the last quarter of the 20th century made it increasingly difficult for photographers to remain content with unquestioning depictions of an increasingly tainted landscape: rapidly accelerating environmental destruction, and the rise of the heritage industry with its inevitable grotesqueries and unintentional black humour. The result has been the development of an oppositional landscape photography which addresses issues of land ownership, power relationships, ecological concerns and uncontrolled commercial exploitation, while also questioning the relevance of the landscape tradition to those hitherto excluded from it.

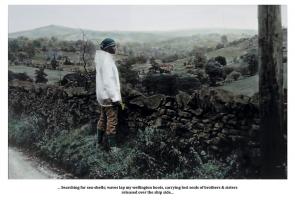

In this context, Martin Parr satirises the tourist industry and its spoliation of the very ‘beauty spots’ it preys on, Clive Landen’s quasi-forensic images of road kills underline the real distance between us and nature, and Chris Wainwright focuses on the oppressive presence of the nuclear industry. Susan Trangmar’s anonymous female protagonist, her back turned obstinately to the viewer, sometimes punctuating and sometimes obscuring a sequence of otherwise deadpan documentary scenes, deconstructs the codes of both landscape and portraiture photography. Finally, Ingrid Pollard’s work touches upon difference and belonging, showing how an essentially conservative view of tradition and heritage can isolate and exclude.

John Stathatos