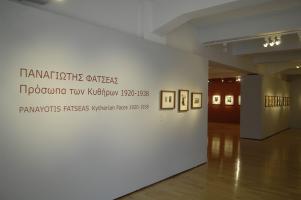

ΠΑΝΑΓΙΩΤΗΣ ΦΑΤΣΕΑΣ

Πρόσωπα των Κυθήρων, 1920-1938

A SMALL FRACTION OF IMMORTALITY

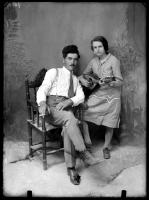

Did Fatseas stage his portraits? We don’t know. Or rather, yes – of course he staged them; but he didn’t practice what is meant today by staged photography. In other words, he didn’t invent imaginary stories or devise alternative realities. On the contrary, the sole purpose of staging was to emphasise the objective nature of those passing before his lens. The way he arranged people in front of the background curtain was a kind of staging, and so was his ever more restrained use of the simple props he allowed himself: the few flower petals scattered on the floor at the feet of the young girls, the carved walking stick flourished proudly by a gendarme, the spring of basil held by a solitary woman, a bouquet, the dog curled up beneath his master’s chair, a long-barrelled shotgun like an old musket. And after all, the way he approached his subjects was itself a form of staging: an approach which instead of intimidating, allowed them to be, quite simply, themselves.

These portraits offer themselves up for deliberate scrutiny, and the eye constantly discovers emotionally and visually charged details which bring an added dimension to the image: the ‘best’ jacket of the young boy whose too-short sleeves hover just above the wrists, the heavy hobnailed boots worn with a formal suit, or the almost but not quite identical dresses worn by two young women of the same family. Alan Trachtenberg’s perceptive comment about Mike Disfarmer, that distant colleague of Fatseas’, applies no less to the Greek photographer: “…his people leap out; nothing distracts attention from them, from the physical details which comprise them and make their bodies and dress and expressions such plausible vehicles of particular lives – the delicacy of a hand touching a shoulder, the twist of an ankle, the tilt of a hat, the rumpled folds of trousers, the fall of cotton dresses on the work-stiffened bodies of country women”.[1]

The Kytherians photographed by Fatseas do not seem like impersonal figures, symbolic perhaps of some nostalgically viewed past, but preserve their individual personalities. The two or three days’ wages which they paid the photographer turn out to have been a good investment, since alongside the postcard-sized prints mailed to a father or son in Australia, they were – all unwittingly – also purchasing a small fraction of immortality. Not just because their faces have travelled down the years to reach us, but above all because the photographer’s alchemy proves such that before these miraculously resurrected photographs, we pause involuntarily to study their image and wonder who they were, how they lived and what passed before their eyes. Immortalised by Fatseas, they are simultaneously other and familiar."

John Stathatos

[1] Alan Trachtenberg, “Disfarmer and Heber Springs”, in Mike Disfarmer, Steidl/Steven Kasher Gallery, Göttingen & New York, 2005, p.19.

Exhibition history

• 2008 Benaki Museum, Athens (21/02-23/03/08)

• 2018 Museum of Byzantine Culture, Thessaloniki (26/09 – 20/10/18)