Alphonse Bertillon and Photography

Eugenia Parry: Crime Album Stories, Paris 1886-1902.

Zurich: Scalo, 2000.

I first came across the photographs of Alphonse Bertillon three years ago in an exhibition curated by Russell Roberts for the Oxford Museum of Modern Art. In Visible Light was an eclectic and wide-ranging meditation on photography and classification which included a variety of images new and old by the famous and the unknown. It seemed to me at the time that one of the exhibition’s subtexts was the juxtaposition of older, often anonymous but invariably functional examples of early photography with work in a superficially similar vein by contemporary photographic artists; the comparison ought to have worked entirely to the benefit of the more glamorous, in-your-face modern work, with its clear advantage in terms of sophistication, size and colour, particularly when seen alongside the smaller, early black and white prints.

Intriguingly, however, the reverse happened; Andres Serrano’s large, glowing mortuary portraits of crime victims were overshadowed by anonymous early 20th-century scene-of-the-crime images from the archives of the New York City Police Department, Jo Spence’s elaborately staged “phototherapy” photographs seemed childish and wilful when compared to Dr Hugh Diamond’s powerful 19th century portraits of the insane at Bedlam Hospital, and Inez van Lamsweerde’s would-be transgressive digital nudes shrivelled before the calm gaze of the whores E.J. Bellocq photographed in New Orleans around 1912. For me, and probably for most viewers, the exhibition’s greatest surprise was the turn-of-the-century photographs of the French criminologist Alphonse Bertillon, eight of which had been loaned by Historical Collections Museum of the Paris Police Prefecture.

Bertillon is of course reasonably well known as an early advocate of scientific criminology, and particularly as the inventor of anthropometry, a method of identification based on recording ten facial and bodily measurements including the width of the left ear, the distance between the left elbow and the middle finger, and the length of the middle finger itself, as well as the colour of the eyes and any abnormal features. The chances of two individuals possessing the same set of measurements were, Bertillon, argued, insignificantly remote. In addition, many of the five million fiches or record cards which Bertillon, as head of Department of Judicial Identity, had accumulated by 1894 included two photographs of the suspect’s face, full on and in profile. What is much less well known is that Bertillon himself often photographed, or in some cases caused to be photographed, the actual sites of major crimes.

Our lack of familiarity with these astonishing images is clearly due to the fact they were judicial documents; not only did it never occur to anybody that they might be seen in a different context, they were also no doubt protected by all kinds of legal impediments and bureaucratic regulations. Nevertheless, it turns out that the Paris Police museum does not have a monopoly of Bertillon’s photographs. Some time before the first world war, an unknown employee of the Prefecture subtracted a number of prints which he mounted in an album and carefully annotated; his choice was, we may assume, governed to a certain extent by the shock value of the photographs. At some point, since there has always been a market for such things, the album ended up in a Paris shop specialising in “curiosities and morbidities”, subsequently passing into the hands of “a grey-eyed man selling fossils in the Paris flea market”, co-owner of an antique gallery. It was here, over twenty-five years ago, that Eugenia Parry stumbled across the album and its contents.

By her own account, Parry was profoundly shocked by the grand-guignolesque nature of some the images, “masses of women’s hair, cut throats, dismembered torsos, sweating slabs, violated interiors disgorging debris… They’re beautiful. They make me sick.” Eventually, her horrified fascination was refined into Crime Album Stories, a series of twenty-five illustrated texts describing a total of forty-three murders which occurred in Paris between 1886 and 1902. Her sources for each case were the tabloid newspapers of the time, some of which concentrated exclusively on the day’s more lurid trials; unlike Michael Lesy, however, in his superficially similar Wisconsin Death Trip, she has fictionalised her accounts, adopting a variety of personae, alternating from an authorial voice to that of a murderess or of Bertillon himself. In an afterword, she reveals that her own father, a Greek-American immigrant to America, was himself a murderer who at the age of seventy “put five bullets” into one of his cronies; Crime Album Stories is dedicated to him.

The crimes she narrates are nearly all crimes of poverty, characterised as much by futility as by the brutality and stupidity of the perpetrators; murderers plot and kill for a handful of coins, leave incriminating clothing at the scene of the crime, fail to wash the victim’s blood off their own bodies, escape in a horse-drawn cart incongruously loaded with a heavy iron safe. Paris at the turn of the century appears to have been an exceptionally violent place, at least until we look further back into history: the setting of Richard Cobb’s classic Death in Paris predates Parry’s by exactly a century, but the crimes he describes, and their protagonists, are identical to those Parry has unearthed: “Most such murders seem to have been confined within the circle of the family: wife-slaying, husband-poisoning, infanticide, […] a few committed without apparent premeditation, in the course of interrupted burglaries… In all these cases there had been no difficulty in identifying the murderer or the murderess, generally known by name and by sight to the whole quarter”. Even the apparently exotic fin-de-siécle dismemberments seem to have formed part of a long tradition; according to Cobb, “the dismembered body of a former garcon-limonadier is discovered,” on Christmas eve 1797, “ the trunk in the rue de la Mortellerie, the head and arms in the rue du Petit-Musc”.

Gripping though it undoubtedly is, I am not wholly convinced by Parry’s creative approach to this material (her acknowledgements include one to the National Endowment for the Arts for a grant in “creative non-fiction”, a category which begs all kinds of questions); while it allows her to invent such lines as “In a surge of animal power I sacrificed Ferdinand”, Cobb’s ironic detachment or Lesy’s deadpan anthologising seem to me in the long run more effective. More seriously, this technique tends to sideline the photographs themselves; one would have liked to see more of them, and been given more information about them.

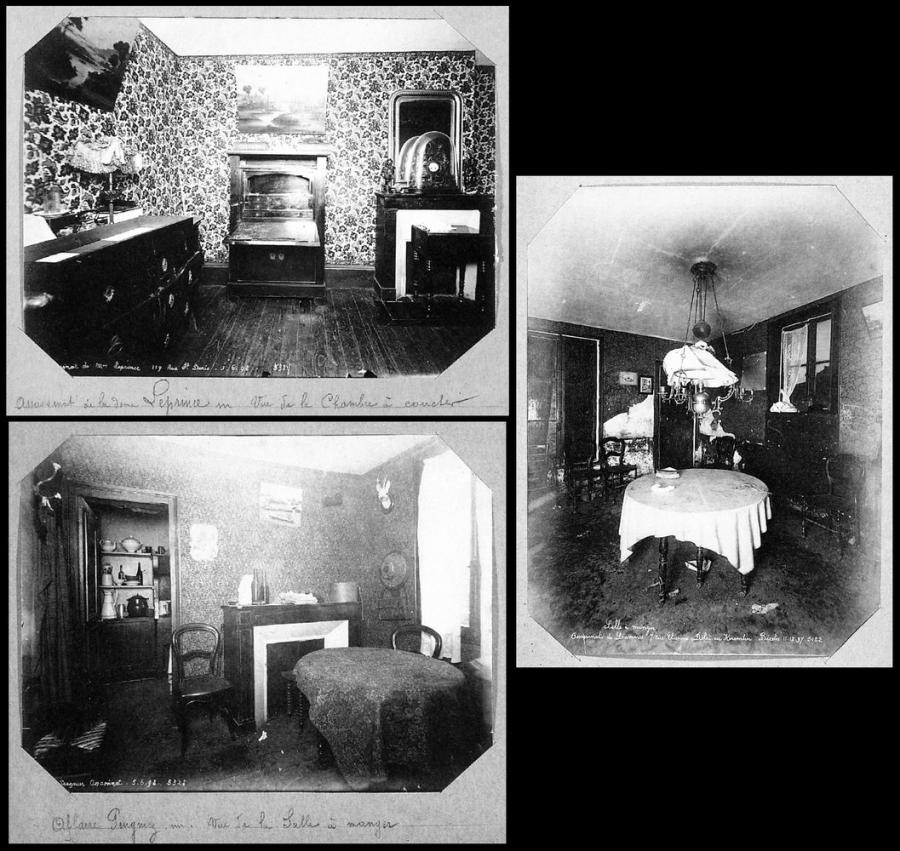

The images reproduced here, almost all of them from the Paris album, now in the Gérard Lévy collection, are of two kinds: a smaller number of purely forensic close-ups of bodies, passably horrific but not particularly interesting precursors of Joel-Peter Witkin (for instance, two prints captioned “Affair of the man cut in pieces, at the morgue” and “Woman’s torso concealed in a suitcase”), and the genuinely fascinating scene-of-the-crime images. The latter, particularly those illustrating interiors, have a hallucinatory quality which is due to something more than their preternatural clarity and depth of field, qualities presumably the result of large negatives, intense lighting and long exposures. They offer nothing as banal as horror; what they communicate is the peculiarly sinister quality of the inanimate running riot, of material objects gone clean out of control.

In the case of the murder of Dr Alaux’s valet, in the rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, we are shown a view of the dentist’s living room stuffed to the rafters with clutter, dominated by a monstrous grand piano muffled in a fringed fabric whose excess verges on the demented, covered as it is in appliqué roses, embroidery, gold lace, bobbles and swaging; compared to that, the body of the valet in the next picture seems almost incidental. In fact, in most cases the body of the victim remains virtually invisible among the plethora of things. The hideous little boxroom in which the young waiter Mathurin Pic was stabbed to death is at the opposite extreme from Dr Alaux’s bourgeois lair, but the photograph taken of it is dominated by the patterned wallpaper and the jumble of clothing and bedclothes piled up on the bed; only slowly (if at all) will the viewer make out the body underneath the jumble, one naked foot thrust against the bars of the bed. The obsessive recording of physical detail, in fact, is reminiscent of nothing so much as the photographs of Atget – but an Atget nightmarishly revisited through the eyes of David Lynch.

© John Stathatos 2000, 2015

First published in European Photography no. 67, Summer 2000