Two and a half thousand years ago, along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, men speculated on the nature of the universe, and their speculations still form part of that intellectual matrix which is European culture. Heraclitus of Ephesus was the last and perhaps greatest of the Ionian pre-Socratic philosophers; ironically, his work survives only in cryptic fragments, ranging from a single word to medium-sized paragraphs. Gathered together, these fragments would barely fill two dozen pages of a modern book, but of them at least has become proverbial in every European language: You cannot step twice into the same river.

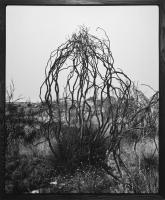

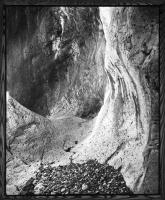

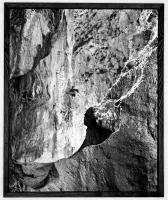

Heraclitus, insofar as we can reconstitute his thought, believed the physical world to be composed of three elements: Fire, Water and Earth. Of these, he held Fire to be the most important as a physical manifestation of the principle of eternal flux, the ceaseless change which characterises the visible world. And the physical universe of Heraclitus, it is worth remembering, was as simple as its intellectual counterpart was sophisticated: that same spare, bony landscape which is still found today in Greece, in Sicily and Asia Minor.

This connection, between landscape and flux, between memory, change and the land, seems implicit in any reading of Heraclitus. In his essay Thoughts on Three Heraclitean Elements, Ivan Gaskell has written: "Change is a procession of many lives, many deaths. Death leaves its mark in memories, memories which flow, ebb and disperse. Each life, each death, leaves its mark, not only in memory, but on the land. A field boundary, a path to a stream, upturned sods, a dusting of ash: the passage of life, of death, is one and the same. The land is the physical register of mankind's transit, in life and death".

Two things above all interest me in the nature of photography. First, the medium's close, almost inevitable relationship to the workings of memory, and second, the inherent ability of photographs to signify more than is represented on the surface of the print or negative - a process of accretion which depends, precisely, on the play of memory, on metaphor and on allusion. In this context, much of my own recent work is concerned with the use of landscape imagery in terms of its cultural and historical associations.

Three Heraclitean Elements (1991) consists of images made within the same few square miles of a Greek island, arranged in three sequences corresponding to each of the elements. The first and third sequences, Fire and Earth, both consist of seven black and white images, drymounted and framed though not glazed; the second, Water, consists of two black and white transparencies of the same size, mounted on light-boxes resting on the floor.

John Stathatos

Description

Fourteen unique silver prints, 135 x 110 cm, drymounted on foamboard and framed (unglazed) in dark grey wood, plus two illuminated transparencies on metal lightboxes. Images from the sequences "Fire" and "Earth" have also been printed in limited editions of 7 (50"x40" or 40"x32") and 15 (25"x20").

Exhibition history

• 1991, Cambridge Darkroom, Cambridge

• 1991, Museum of Art, Ein Harod, Israel

• 1992, "Du paysage européen", Rencontres Internationales de la Photographie, Arles, France

• 1993, F-stop Gallery, Bath, UK

• 1994, Porfolio Gallery, Edinburgh, UK

• 1996, “The Invention of Landscape”, Photosynkyria, Thessaloniki, Greece

• 1997, Burford House, Shropshire, UK

• 1999, Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art, Thessaloniki, Greece

Bibliography

• John Stathatos: Three Heraclitean Elements, CDR Publications, Cambridge 1991

• Catalogue, "Du paysage européen", Rencontres Internationales de la Photographie, Arles 1992

Collections

Two prints from "Fire" are in the permanent collection of the Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art