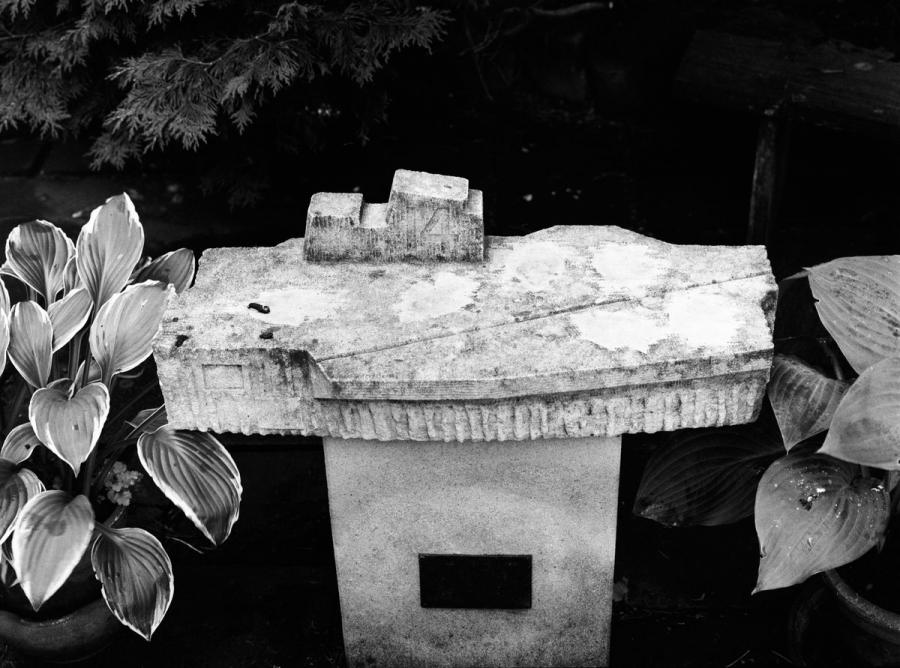

Folksongs, even when they deal with the fantastic, are almost always grounded in ‘common’ sense. When a ballad asks “how many ships sail in the forest?”, it does so with ironic intent, begging the answer “none”; but in Little Sparta, the correct answer is “quite a few”, for the seas of its thickets and woods are sailed by aircraft carriers, while nuclear-powered submarines cruise fathoms deep beneath the surface, only their conning-towers breaking above the green turf. Ian Hamilton Finlay’s stone battleships are amongst his most powerful and enduring creations. The image of a petrified ship, stranded high and dry above the tide-line, is both poetically and visually powerful, its lineage as ancient as the oldest extant Greek text and as contemporary as Ian Banks’ science-fiction novel Use of Weapons.

The concept is at heart an oxymoron, a flouting of the common sense exemplified, as it happens, by Finlay’s English Colonel in the second Orkney Lyric from The Dancers Inherit the Party:

The boat swims full of air.

[...]

The hollowness is amazing. That’s

The way a boat

Floats.

But such is not the case with these boats, nor is it for their many cousins in the Mediterranean. The coasts of Greece and Italy are full of petrified ships, boat-shaped rocks and reefs whose presence hints at supernatural intervention: here a shipful of pirates turned to stone by Saint Demetrius, there a galley frozen by vengeful nereids. Inexplicably, a perfectly formed Chinese junk lies frozen off the south coast of Cythera. The tradition is an old one, for both Homer and Apollodorus tell of how, through the malice of Poseidon, the kindly Phaeacian ship which carried Odysseus to Phorcys was turned to stone with all her crew.

By name at least, Finlay’s fleet acknowledges a later patrimony, since there are no fewer than four works entitled Homage to the Villa d’Este in Little Sparta, two by the edges of the Temple Pool (Aircraft Carrier Fountain and Aircraft Carrier Bird-Table), and two in the Roman Garden (Aircraft Carrier Bird-Bath and Aircraft Carrier Torso). They refer, of course, to the elaborate sixteenth-century water gardens designed for Cardinal Ippolito d’Este at Tivoli, in the Roman Campagna, in which ships make two appearances; first as a convoy of twenty-two small boat-shaped fountains along the Alley of the Hundred Fountains, now almost entirely obscured by thick moss, and then, more impressively, in the form of a galley bearing an obelisk in the Fountain of Rome.

Boats are not otherwise particularly common in Italian Renaissance gardens, and when they are encountered it is almost always in association with fountains; the Villa Lante at Bagnaia has four particularly splendid examples. The seventeenth century added a few more, including the Fontana della Barca at the Villa Aldobrandini in Frascati. However, Giovanni Rucellai’s description of his garden at the Villa Quaracchi in Florence includes an account of fantastic boxwood topiary in the shape, amongst many others, of ships and galleys.

Finlay’s aircraft carriers, one (the fountain) in bronze, the others in stone, are an elegantly erudite twentieth-century echo of this almost forgotten tradition. Great gardens such as Little Sparta and the Villa d’Este are, among other things, sites of cultural commemoration and recapitulation; as Jean Starobinski reminds us, “the garden [is] a country of the memory”. Designed at the time of the first western rediscovery of classicism, the Villa d’Este is replete with references to Hercules, from whom the d’Este family claimed a mythical descent, and to ancient Rome, a substantial model of which dominates the piazza at the end of the Alley of the Hundred Fountains; in its turn, Little Sparta, cradle of the third neoclassical revival, pays appropriate homage to its predecessors by means of these sculptures.

Formal art-historical links of this kind are important, since a site like Little Sparta does not evolve in a cultural vacuum; nevertheless, as is the case with much of his work, the emotional power of Finlay’s warships lies largely elsewhere, and is immediately apparent to even the most untutored of visitors. Above all, of course, is the idea of the garden as metaphor for the sea, a metaphor explicitly proposed by the Mare Nostrum plaque and endlessly elaborated throughout Little Sparta. Wherever the ships have been placed, but particularly in the Roman Garden, the metaphor is extended visually by foliage (smooth, lanceolate leaves mimicking rolling waves, while evergreen fronds take on the appearance of foam), and aurally by the sound of wind rustling in the branches, a sound so uncannily like that of running water, or the ebb and flow of surf.

Finally, there are those puns, a mixture of the visual and conceptual, at once immensely sophisticated and artlessly self-evident, which are so characteristic of Finlay; for who could resist the conceit of an Aircraft Carrier Bird-Table or Bird-Bath whose upper surface (or flight deck) serves as a launching pad for chattering members of the finch and sparrow family? Fly Navy indeed!

© 1994 John Stathatos

First published in Chapman 78/79, October 1994